Parliamo delle tech news. Quei titoli clickbait sul lavoro spazzato via dai robot ho smesso di leggerli da tempo. E ho scoperto di non essere il solo a sospettare della bontà delle daily news: John Zeratsky di GV (Google Ventures) racconta di come sia possibile rimpiazzarle con una dose di The Economist a settimana. Jason Fried, fondatore di Basecamp, racconta invece del suo periodo di disintossicazione da Tech Buzz.

Osservare ciò che accade nel settore tecnologico per noi è troppo importante. Così importante da rischiare di rimanerci intrappolati, in quel buzz. Seguendo tutto, spesso senza arrivare a nessuna conclusione.

Il nostro lavoro è progettare sistemi basati sulla tecnologia, abbiamo imparato da qualche tempo ad assumere un atteggiamento cauto rispetto ai cicli di cambiamento tecnologico. Lo abbiamo visto con Google Glasses, con gli occhialini 3D per guardare la televisione e molto probabilmente presto anche con gli schermi curvi.

Ciò che abbiamo imparato negli ultimi due anni di lavoro è che l’innovazione tecnologica da sola non basta: la sfida è progettare qualcosa di nuovo che sia realmente utile.

“La tecnologia ha valore quando capiamo come le persone possono utilizzarla e ottenere benefici reali.”

Nancy Duarte — Scrittrice, TED Speaker, CEO di Duarte

I prodotti innovativi esistono, ma per trovarli e progettarli bisogna sapere guardare oltre il buzz.

Alcuni di questi prodotti nascono da una visione così chiara e vicina alle nostre esigenze e ai nostri desideri che subito ci colpiscono sul piano emotivo. Le storie dei fondatori di queste aziende ci ispirano, ci identifichiamo con il desiderio di migliorare il mondo.

“In una startup, i fondatori definiscono la visione di prodotto e da lì partono alla ricerca del mercato.

Steve Blank — Imprenditore e autore del best seller “The Four Steps To The Epiphany”

Molti di noi vorrebbero essere il prossimo Jeff Bezos. Ma la realtà è che fare innovazione è tremendamente difficile.

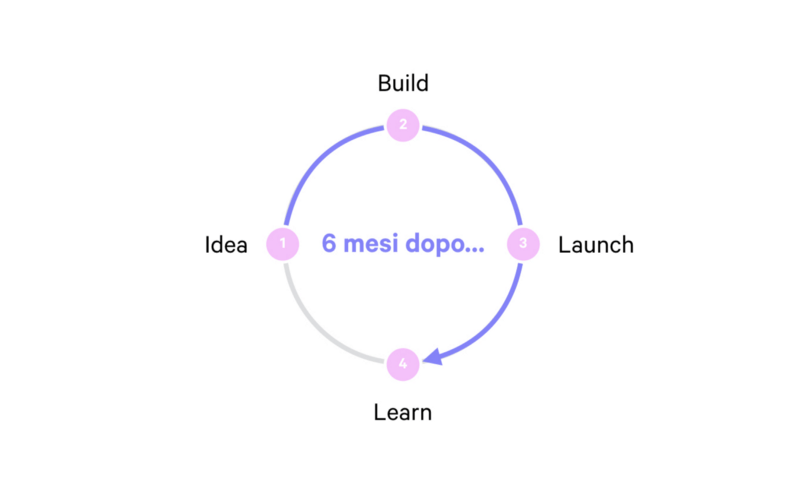

Il fallimento per un prodotto innovativo è per definizione un evento ad elevata probabilità. Un contributo fondamentale che mira ad aiutare gli innovatori di tutto il mondo nel costruire nuove imprese è stato dato dal movimento Lean Startup, grazie al celebre libro di Eric Ries.

La filosofia Lean Startup ci insegna la differenza tra costruire un prodotto solido (build the product right) e costruire il prodotto giusto (build the right product).

Questo passaggio è stato il focus di attenzione dei nostri ultimi anni in Moze nel realizzare prodotti software per i nostri clienti. Durante i primi anni della nostra impresa abbiamo avuto la fortuna di lavorare a molti progetti: eravamo bravi e rapidi nel realizzare siti e applicazioni belli, piacevoli per estetica e stile.

In quel periodo abbiamo affiancato Wanderio — startup italiana nel settore travel — nella sua fase di crescita iniziale. L’amicizia e la partnership con Wanderio ci hanno permesso di comprendere in profondità le dinamiche di progettazione e sviluppo di un servizio digitale in continua evoluzione.

Build the product right

Erano gli anni in cui abbiamo imparato a costruire un prodotto solido a partire da una lista di specifiche di funzionamento. Abbiamo imparato a lavorare in team, creando un vocabolario comune tra designer e developer.

Abbiamo imparato che progettare vuole dire creare una soluzione per risolvere un problema.

Tutti i progetti allora iniziavano quasi sempre da un documento di specifiche (il brief), con la richiesta di implementare un lista di funzionalità software.

Notavamo che molti dei progetti che miravano a creare prodotti innovativi seguivano un pattern ricorrente:

- Il brief: un documento scritto dal cliente, ricco di dettagli per descrivere cosa il prodotto dovrebbe permettere di fare.

- Lo sviluppo: il software viene progettato e sviluppato — solitamente in molti mesi di lavoro.

- Il lancio: il prodotto viene rilasciato al pubblico con un grande annuncio.

Purtroppo in più di un’occasione ci siamo accordi che a quel punto qualcosa non andava. Al momento del lancio non c’era ad attendere il prodotto la fila di persone che ci si aspettava.

Ci siamo presto resi conto che non era un problema unicamente nostro e dei nostri clienti: secondo una recente ricerca di CBInsights il 42% delle startup falliscono perché non c’è domanda da parte del mercato.

Nel 42% dei casi un’azienda sta lavorando ad un prodotto innovativo di cui nessuno ha bisogno.

Spesso il punto di partenza di un progetto è la soluzione: l’insieme delle tecnologie, le funzionalità da implementare.

Abbiamo imparato, un po’ alla volta, ad iniziare ogni progetto focalizzando l’attenzione non sulla “soluzione” ma sul problema da risolvere.

Per fare questo abbiamo trovato aiuto in una tecnica chiamata Jobs-to-be-done, che analizza i compiti (Jobs), cioè i bisogni delle persone a cui un prodotto si rivolge.

Il principio alla base di questa tecnica è il progresso, inteso come naturale tendenza delle persone a cercare un qualche tipo di avanzamento nella propria vita (funzionale, emotivo, sociale).

Azione, motivazione, casualità e ansia

Acquistiamo un mazzo di rose. Il motivo per cui lo facciamo (il nostro “Job”) è tutto fuorché funzionale: vogliamo farci perdonare di essere rimasti in ufficio a lavorare fino a tardi. Durante il tragitto casa-lavoro siamo inchiodati agli schermi del nostro smartphone. Ciò che facciamo realmente però è tenere la mente impegnata in giochi, o leggendo notizie. Prendiamo un aereo, ma lo facciamo per ricongiungerci con la nostra famiglia e passare del tempo di qualità insieme.

Prima di tutto, quindi, è importante chiarire quali sono i “Job” che vogliamo soddisfare. Jeff Bezos è famoso per aver detto che i bisogni delle persone non cambiano nel tempo.

Ciò che cambia, anche grazie alla tecnologia, sono invece i prodotti che vengono usati per soddisfare quei bisogni.

Allora, se creare un nuovo prodotto vuol dire sfruttare un bisogno già esistente, noi designer dobbiamo convincere le persone ad abbandonare la soluzione attuale e desiderarne una nuova.

Il Jobs-to-be-done utilizza uno schema chiamato “Force Diagram” (schema di forze) per capire quali forze positive e negative influenzano i potenziali clienti nell’adozione di un nuovo prodotto.

Nel 2009 Apple con la sua campagna “Get a Mac” ha offerto uno degli esempi che rappresentano al meglio l’utilizzo consapevole dello schema di forze in gioco nella scelta di un nuovo prodotto. Si tratta di una serie di sketch pubblicitari che presentano il tema ricorrente di un giovane ragazzo affabile (Mac) messo a paragone con un uomo goffo (PC).

Intervistare potenziali clienti permette di identificare le forze in gioco nella scelta di un prodotto. In questo modo possiamo:

- Generare ipotesi progettuali.

- Sfruttare il brand per parlare alle emozioni delle persone.

- Ideare nuove funzionalità che rendono più facile, veloce o efficace la risoluzione di un problema.

Grazie alla tecnica del JTBD oggi affrontiamo ogni nuovo progetto chiedendoci prima di tutto a quale “Job” vogliamo rispondere.

Il JTBD è una tecnica “open” totalmente flessibile. Ci sono inoltre molte risorse disponibili gratuitamente per imparare a mettere in pratica questa metodologia.

Comprendere a fondo le implicazioni riguardo il “Job” da risolvere permette di concentrare le energie sulla soluzione più efficace.

Cercavamo un modo per accorciare il tradizionale ciclo di sviluppo e rilascio, per mettere alla prova il concept di prodotto grazie a feedback e reazioni dei potenziali utilizzatori prima ancora di iniziare lo sviluppo tecnologico.

Mentre cercavamo un modo migliore di approcciare la generazione di soluzioni, GV (Google Ventures) rendeva pubblico il Design Sprint: un processo di design per aiutare le aziende tecnologiche a validare rapidamente idee di business.

Il Design Sprint è una sorta di macchina del tempo: permette di fare un balzo avanti prima di impegnarsi in lunghi cicli di sviluppo. Aiuta ad ottenere reazioni spontanee dai potenziali utilizzatori andando a creare, in soli cinque giorni, un prototipo realistico.

Nel Design Sprint viene creato un unico team di lavoro che include le figure chiave dell’azienda o del team di prodotto: business, marketing, design, engineering, customer support.

Il primo giorno del Design Sprint è dedicato ad allineare il team di lavoro verso il problema che si vuole risolvere, ad analizzare lo scenario competitivo e la ricerca fatta fino a quel punto.

Il secondo giorno si generano soluzioni alternative, disegnando concept progettuali che saranno messi a confronto il terzo giorno, in cui si convergerà verso una sola soluzione. Il quarto giorno viene costruito il prototipo che, durante il quinto giorno, viene testato dal vivo con potenziali utilizzatori.

Le energie del team durante un Design Sprint sono focalizzate ad apprendere il più possibile dalle reazioni degli utenti, piuttosto che a creare il prodotto perfetto. Questo è possibile anche grazie a strumenti che permettono di creare un prototipo realistico in poco tempo, come ad esempio InVision per creare prototipi di UI interattivi, o Typeform e Botsociety per progettare interfacce conversazionali (chatbot). Perché iniziamo ogni nuovo progetto con un Design Sprint.

Per concludere: oltre il Tech Buzz, oltre i Tool

Abbiamo raccontato come le daily news di settore possano distrarci, di come la chiave del successo stia ancora nel sapere come sfruttare le tecnologie emergenti per creare un prodotto realmente utile per le persone.

Volevamo aiutare i nostri clienti a creare un prodotto digitale utile per i loro utenti. Nella nostra esperienza, studiare e applicare tecniche come il JTBD e il Design Sprint contribuisce a diminuire i rischi legati all’avvio di un nuovo progetto (Steve Blank definisce una startup come «un’azienda che opera in condizioni di estrema incertezza»).

Nel nostro caso circa il 70% dei progetti iniziati con un Design Sprint ci ha visto riformulare il concept previsto inizialmente con l’obiettivo di evitare di costruire un prodotto basato solamente su ipotesi.

Vorremmo lasciare un messaggio finale in grado di andare oltre non solo al buzz delle notizie di settore, ma anche ad un focus esclusivo sugli strumenti e le tecniche di design: quando dieci anni fa imprenditori in tutto il mondo si trovavano a creare prodotti e servizi tecnologici c’era molta meno conoscenza di oggi.

Anno dopo anno, professionisti e imprenditori hanno iniziato sempre più frequentemente a divulgare parte della loro ricetta segreta.

Ciò non significa che oggi creare un’impresa tecnologica di successo sia più facile che in passato, vuol dire però che oggi abbiamo molti più strumenti e conoscenza condivisa per determinare se la nostra impresa si trova sulla strada giusta, investendo risorse là dove esiste l’evidenza misurabile del successo.

Queste sono le cose che abbiamo imparato fino ad oggi, in un percorso in continua evoluzione. Oggi che è ormai diventato impossibile stare al passo con le tech news, e dove il rumore di fondo rischia di distrarci dalle vere opportunità, essere buoni progettisti — o designer — rappresenta ancora il modo migliore per portare progresso e innovazione alle persone attraverso la tecnologia.